By Carol Kino

By Carol Kino

Can artists control the way history records them? How do some manipulate their legends – and what fate befalls those who can’t, or who loathe the very idea?

Such questions, fodder for much contemporary art gossip and art historical research, fuel “The Killing Art,” by Jonathan Santlofer, a New York painter who has increased his own fame and fortune recently by writing murder mysteries set in the New York art world.

Unlike his previous two books, however, Mr. Santlofer’s new tale is rooted in a real-life art historical episode: a gathering of Abstract Expressionist artists in April 1950. There, the unpleasant reality unfolded that by the end some artists would be in and some out. And the anointed were depicted a few months later in an iconic photograph in Life magazine.

That meeting has been documented, most recently in “De Kooning: An American Master,” a 2004 biography by Mark Stevens and Annalyn Swan. According to the authors, it was actually a three-day symposium at which the artist Robert Motherwell and Alfred Barr, then director of the Museum of Modern Art, pressed the assembled artists to define what differentiated their work from what had come before.

What is unusual in the novel’s rendition is that the story is related from the viewpoint of artists who ended up on history’s wrong side. As Mr. Santlofer put it, “The selection process, more than anything, is what triggered my idea.”

Once again, the heroic protagonist is Kate McKinnon, a glamorous, successful art critic who, before she married money, was a homicide detective in Queens. Improbable though Kate may seem, the killers she pursues are always entirely believable, at least from a critic’s perspective: artists desperate enough to do anything, however lunatic, to nab attention for their work.

In Mr. Santlofer’s first novel, “The Death Artist” (2002), Kate hunted down a wannabe Damien Hirst who used his victim’s bodies to recreate famous artworks. In the second, “Color Blind” (2004), she sought an outsider artist who could only see color when the media included fresh blood.

This time, the culprit who lures her out of law-enforcement retirement begins by slashing up Abstract Expressionist canvases, and is soon turning the X-Acto knife on any hapless artist, collector, museum curator or heir who gets in the way.

Providentially, Kate is working on a book about the Abstract Expressionists as well as a public television series for which she must interview surviving members of the group. (In the first chapter, she has just typed the fatuous phrase, “It was a time of intense friendship and camaraderie.”) And after donning her detective hat to help the New York Police Department’s art squad, she realizes that the solution to the mystery lies buried in art history. How many artists other than de Kooning painted the human figure? Why did some abstractionists rise during that period, while others virtually disappeared?

This gambit allows Mr. Santlofer to spoon-feed the reader heavy doses of Abstract Expressionist history, some of which is true and some of which is not.

Many of the characters – and all of the slashed paintings and people – are inventions or composites. Yet several, like Jackson Pollock, Franz Kline and the teacher Hans Hofmann, are real, like Kate’s most unsettling discovery: the meeting of the major Abstract Expressionist players.

Mr. Santlofer, 58, said that he learned about the meeting in 1990 while interviewing Milton Resnick and several other second-generation Abstract Expressionist painters, including Grace Hartigan, George McNeil and Hedda Sterne, for ArtNews magazine. Like Kate, he said, he had embarked on his research with “a very romanticized view of the period.”

But while reporting, he was dismayed to find that “in fact it was filled with competition and jealousy.”

“Fame and success broke us up,” he was told by Ms. Sterne, the only female painter to make the cut for the Irascibles, the group photographed for Life by Nina Leen. “She said she sat back and watched the men drink and compete and have heart attacks and die.”

But the most interesting revelation, he said, surfaced in a chat with Mr. Resnick, the cantankerous abstractionist who began including faint figures in his paintings late in life, decades after his career had been overshadowed by that of de Kooning, a close friend. During the interview, Mr. Santlofer said, Mr. Resnick told him about a meeting of Pollock, Ad Reinhardt, Motherwell and others, shortly before the group became known as the Irascibles.

“They wanted Milton in the group,” Mr. Santlofer recalled, “but he wanted no part of it. He said to me, ‘I turned to Bill de Kooning, my best friend, and said, “You couldn’t possibly go along with this, could you?” ‘ ”

It wasn’t so much the idea of this event that surprised him, Mr. Santlofer said, but the fact that it had never been part of the Abstract Expressionist legend he had been imbibing since art school. And Mr. Resnick “related it to me in a very bitter, bitter way,” he added.

So he questioned Mr. McNeil, who had been his mentor and his painting teacher at the Pratt Art Institute. In 1936 Mr. McNeil had helped found the American Abstract Artists, an earlier artists’ association that the Irascibles wanted no part of. He told Mr. Santlofer matter-of-factly, “I wasn’t at the meeting; I was pushed out.”

Although neither Mr. McNeil’s nor Mr. Resnick’s career was truly destroyed by the meeting, Mr. Santlofer said, he began to ponder what the effects might have been for others. “What would have happened if one of those people was so excluded that their career and life was ruined?” he said. “What sort of ramifications would there be?”

In one sense, it was Mr. Santlofer’s own sense of ruination as a painter that turned him toward fiction. He began writing 16 years ago, after six years’ worth of his work was destroyed in a gallery fire in Chicago, one night after the exhibition opened. At the time, he said, “I felt like my life was over.” Oddly, “The Killing Art” opens with a scene in which a despairing artist sets fire to himself and his opus – a coincidence he didn’t catch until a friend who read the manuscript pointed it out.

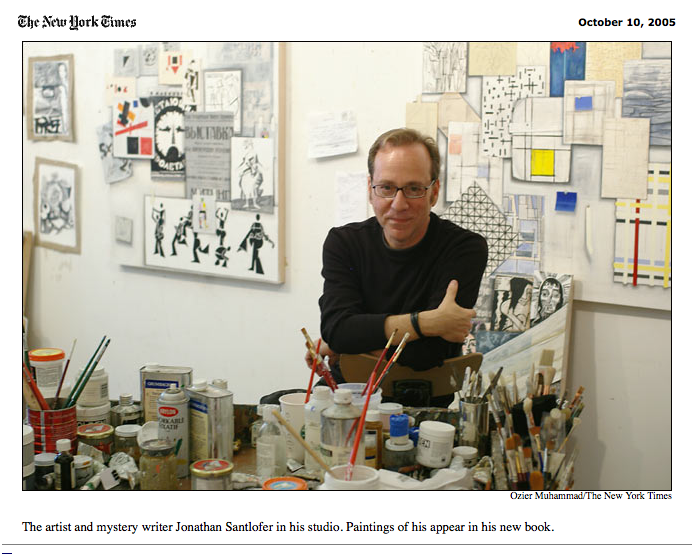

When he began writing, Mr. Santlofer also made a Resnick-esque switch from abstraction to representation, a move that was noted by art magazines at the time. Today his paintings tend to replicate high-profile figures of 20th-century art and pop culture, usually mixed in Photoshop-like fashion; as luck would have it, his killer’s work does, too.

“The Killing Art” is liberally illustrated with the fictional artist’s black-and-white “clue paintings.” Their collaged elements – copies of the invented Pollocks, de Koonings, Klines and so on that are slashed in the book – predict coming attacks. (In reading, one tends to examine this evidence much as Kate does, searching for clues.)

Mr. Santlofer, not his character, made the paintings. One will even appear in his next show, which opens at Pavel Zoubok Gallery in Chelsea on Thursday, two days after the book comes out.

In another twist on the promotional photographs that threatened to splinter Abstract Expressionist friendships, Mr. Santlofer’s status as a “real” artist with a genuine gallery career has been a boon to his publisher, William Morrow, which has used it to promote his books. His author photos always depict him in his studio, surrounded by paint, canvas and brushes.

In an unusual marketing ploy, Morrow will offer another painting from the book as the prize tomorrow, when the book goes on sale, in an online sweepstakes in which entrants must answer questions about the book.

One drawback is that Mr. Santlofer may become far better known for his writing than for his paintings. But, as he recalled, “George McNeil used to say this wonderful thing when people complained about their art life: ‘Nobody makes you do it.’ ”

(View original article here.)