Adam Kirsch, Deborah Treisman, AM Homes, Beena Kamlani, Colum McCann, me, Norma Manea

A great night of Bellow readings to a SRO crowd at Housing Works NYC.

Beena Kamlani, Saul Bellow’s last editor, who put the event together, introduced the evening with a few personal stories about working with the author later in his life. The poet and literary critic, Adam Kirsch, read an evocative passage from Henderson the Rain King. Romanian writer, Norman Manea, read from an interview he conducted with Bellow. The New Yorker fiction editor, Deborah Treisman, talked about editing Bellow and also read, proving she reads as beautifully as she edits; the terrific writer A.M. Homes read a beautiful short story; and the Irish writer Colum McCann was a knock out reading Bellow in his beautiful Irish brogue. Then it was my turn. I didn’t think it was quite fair to make me follow McCann, sort of like following Bono, which I actually said. Here’s the rest of what I said and read—

My father was not one for reading.

A tough boy from Queens stuffed into hand-made suits, a “garmento,” one of those garment center men with a pinky ring and slicked-back hair, a dandy but in no way effeminate. He was macho to the nth degree, steely and driven and not given to self-reflection with a propensity for darkness.

I must have been 14 when I saw Herzog on his bedside table. Like I said he was not a reader, unless it was Golf Digest or Sports Illustrated, so I was fascinated—a book! And I asked him about it.

“It was a gift,” he said.

“What’s it about?” I asked.

He paused, “A crazy man.”

“Really?” I said. “Do you like it?”

This was already one of the longest conversations I’d ever had with my father.

He paused again. “I’m not sure if I like it. It’s got a lot of words but… it’s interesting.”

The book remained on his bedside table for well over a month. I checked it every day, the folded down corner of a page inching toward the end. I was dying to read it – this book about a crazy man that my father found interesting. I imagined that if I read it I would understand my father, that somehow his cool and distant personality would suddenly be revealed to me.

And so, finally, I did read it. Of particular interest to me was Herzog’s following description of his father…

As for my late unlucky father, J. Herzog, he was not a big man, one of the small-boned Herzogs, finely made, round-headed, keen, nervous, handsome. In his frequent bursts of temper he slapped his sons swiftly with both hands. He did everything quickly, neatly, with skillful Eastern European flourishes: combing his hair, buttoning his shirt, stropping his bone-handled razors, sharpening pencils on the ball of his thumb, holding a loaf of bread to his breast and slicing toward himself, tying parcels with tight little knots, jotting like an artist in his account book. There each canceled page was covered with a carefully drawn X. The is and 7s carried bars and streamers. They were like pennants in the wind of failure. First Father Herzog failed in Petersburg, where he went through two dowries in one year. He had been importing onions from Egypt. Under Pobedonostsev the police caught up with him fore illegal residence. He was convicted and sentenced. The account of the trial was published in a Russian journal printed on thick green paper Father Herzog sometimes unfolded it and read aloud to the entire family, translating the proceedings against Ilyona Isakovitch Gerzog. He never served his sentence. He got away. Because he was nervy, hasty, obstinate, rebellious. He came to Canada, where his sister Zipporah Yaffe was living. In 1913 he bought a piece of land near Valleyfield, Quebec, and failed as a farmer. Then be came into town and failed as a baker; failed in the dry-goods business; failed as a jobber; failed as a sack manufacturer in the War, when no one else failed. He failed as a junk dealer. Then he became a marriage broker and failed—too short-tempered and blunt. And now he was failing as a boot-legged on the run from the provincial Liquor Commission.

My father was not at all a failure though I think he lived in fear of failing. The son of stern, unsmiling Holocaust survivors, he seemed to me always worried about… something.

I don’t think the novel revealed anything about my father, but it did cement my love of Saul Bellow. When I told my father I’d read it he said “Interesting, right?” and I said, “Yes.”

One last thing Bellow gave us, a private joke. Throughout the novel Moses Herzog writes letters. I didn’t know most of the people he was writing to and had to look them up, and I discovered my father had done the same thing. Neither me at 14, nor my father at 40 knew who Heidegger was and had looked him up.

Here’s Herzog’s letter:

Dear Doktor Professor Heidegger, I should like to know what you mean by the expression “the fall into the quotidian.” When did this fall occur? Where were we standing when it happened?

Periodically my father would wink and say, be careful not to fall into the quotidian, and I’d always laugh, no matter how many times he’d said it. It was our only joke.

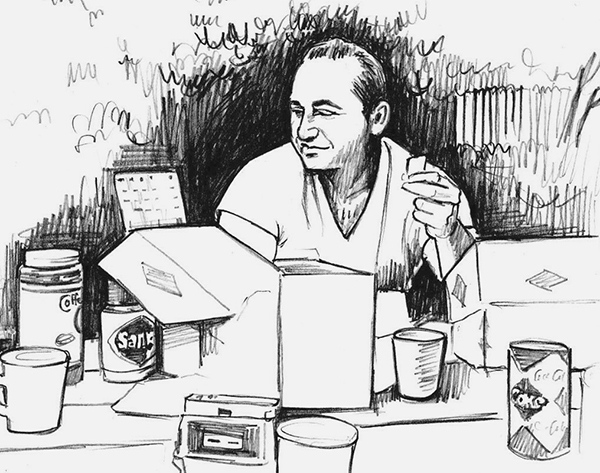

Talking about my father inspired me to do a sketch of him. Here, he is not in his garmento garb, but surrounded by food at our usual Sunday summer night cookout.